The EU Packaging Regulation (PPWR – current text available HERE) will revolutionize packaging law, similar to the EU Battery Regulation already in force. The previous focus of the Packaging Directive 94/62/EC on the area of extended producer responsibility under waste law will be broken up and transformed into a life cycle regulation. In future, the focus will also be on the design and manufacture, as well as the reuse and refilling of packaging in order to minimize the enormous volume of packaging and the constant increase in packaging waste in the EU.

I. Scope of application and roles

First of all, it can be stated that the newly formulated definition of packaging in Art. 3 No. 1 PPWR should not lead to any relevant changes in the determination of the scope of application compared to the existing definition in the Packaging Directive (see recital (10) PPWR). Accordingly, packaging continues to be any “item, irrespective of the materials from which it is made, that is intended to be used by an economic operator for the containment, protection, handling, delivery or presentation of products to another economic operator or to an end-user, and that can be differentiated by packaging format based on its function, material and design”. There are no general exemptions from the scope of application, but there are some duty-specific exemptions, in particular for so-called contact-sensitive packaging in accordance with Art. 3 No. 10 PPWR. This applies, for example, to packaging for medical devices, cosmetic products, medicinal products and foodstuffs.

In contrast, the new PPWR brings with it numerous new responsibilities and, consequently, roles previously unknown in packaging law. At the heart of the new requirements for sustainability, labeling and conformity assessment is the newly introduced manufacturer of packaging. According to Art. 3 No. 14 PPWR, this is any “person who manufactures packaging or a packaged product”. In other words, either the person who produces an empty carton or the person who packs their product into this empty carton. While both parties can certainly be considered responsible in the abstract, the PPWR leaves it completely open in which cases one party should be considered the manufacturer and in which cases the other party should be considered the manufacturer in practice. The only thing that should be clear is that not both actors can be regarded as responsible manufacturers of the same packaging. Comparable delimitation difficulties are also foreseeable for suppliers (Art. 3 No. 16 PPWR – “person who supplies packaging or packaging material to a manufacturer”), importers (Art. 3 No. 17 PPWR) and distributors (Art. 3 No. 18 PPWR). This demarcation of roles is not merely theoretical but has a direct impact on the different responsibilities and the labeling of packaging. It therefore remains to be seen whether the EU legislator will provide further clarification in order to ensure the necessary legal certainty for the entire packaging industry.

II. Sustainability and labeling

As already indicated, Art. 5 et seq. PPWR introduce numerous new obligations for the design and labeling of packaging. An overview of these is presented below:

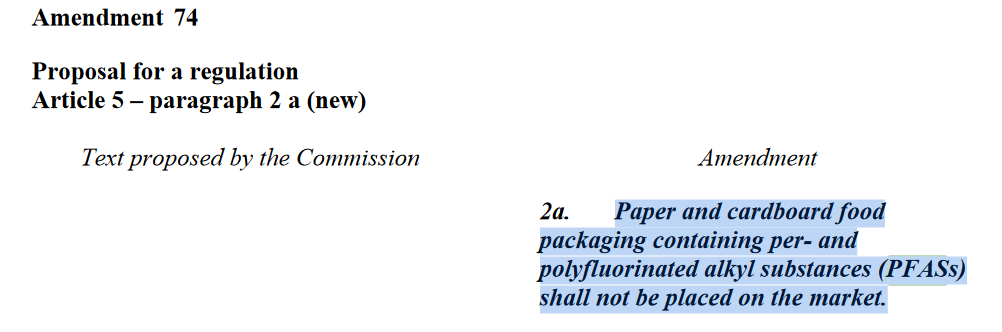

- The existing substance restrictions for packaging are initially continued in Art. 5 PPWR. These are the specific restrictions for lead, cadmium, mercury and hexavalent chromium and the reference to the substance restrictions generally applicable to packaging from other legal acts, in particular the REACH and POP Regulation. What is completely new, however, is the restriction in Art. 5 para. 5 PPWR for PFAS in packaging that comes into contact with food.

- Art. 6 PPWR introduces requirements for the recyclability of packaging. The two criteria of recycling-oriented design (from 2030) and recyclability on a large scale (from 2035) are relevant here, both of which must be specified in further legal acts. If the respective performance classes according to Annex II PPWR are not achieved, the packaging will no longer be marketable in future. Exceptions to this are provided for packaging specified in Art. 6 para. 11 PPWR, in particular for medicinal products and medical devices.

- Another innovation is the mandatory introduction of minimum recycled content in plastic packaging from 2030 (Art. 7 PPWR). Although these must be recovered from consumer plastic waste, they do not have to be met for each individual item of plastic packaging, but only in relation to a specific business per year. Certain packaging for medicinal products and medical devices, among others, are also exempt from this obligation. In addition, all packaging with plastic content of less than 5% of the total weight is exempt.

- Various measures are also intended to avoid unnecessarily large packaging in future. Firstly, Art. 10 PPWR stipulates an obligation to minimize all packaging in terms of its weight and volume. From 2030, manufacturers must therefore use the various performance criteria from Annex IV PPWR to determine and justify why a specific packaging must have exactly the intended weight and volume. In this context, Art. 24 PPWR also introduces a ban on excessive packaging from 2030, which relates to the ratio of empty space between packaging and packaged goods. Finally, Art. 25 in conjunction with Annex V PPWR prohibits certain packaging formats, including numerous types of disposable packaging in the hospitality sector.

- Art. 11 and 26 et seq. PPWR contain complex and so far not always consistent obligations regarding the reusability and refillability of certain packaging.

- Finally, Art. 12 PPWR lays the foundation for uniform EU-wide material labeling, as well as for further labeling on the compostability, deposit requirement and reusability of packaging. Together with the obligation to label waste containers accordingly, this should lead to less waste being thrown away in the future and better recycling results can be achieved through improved collection. This should also clear up the increasingly dense jungle of national labeling requirements, such as the now well-known TRIMAN from France, as these are likely to become inadmissible once Art. 12 PPWR comes into force. However, this will probably not be the case before 2029, as Art. 12 PPWR will only apply three and a half years after the regulation comes into force, provided that the implementing act defining the details of the label is promulgated in good time. From a formal point of view, the label must generally be affixed directly to the packaging and can be supported by additional information in QR codes. It should also be noted that the labeling must be available to the end consumer in online trade before the product is purchased, which ultimately means that it must be displayed either on product images or separately. Finally, reference should also be made to Art. 14 PPWR, which contains specific requirements for environmental claims on packaging.

All requirements from Art. 5 to 12 PPWR will in future be subject to a newly introduced conformity assessment obligation by the responsible packaging manufacturer. The conformity assessment must be based on technical documentation for each packaging and must be carried out as part of an internal production control (without the involvement of a notified body). The conformity of packaging must then be confirmed by means of an EU declaration of conformity in accordance with the model in Annex VIII PPWR. However, a separate CE marking for packaging will not be introduced (see recital (109) PPWR).

III. Further obligations of economic operators

In addition to the obligations described above, manufacturers must in future ensure in particular that all their packaging bears a type, batch or serial number and is labeled to identify the manufacturer (name/trade name/trademark, postal address and, if applicable, electronic means of communication) (Art. 15 para. 5 and 6 PPWR). Importers are also subject to a comparable labeling obligation in accordance with Art. 18 para. 3 PPWR.

All actors in the supply chain, i.e. manufacturers, importers and distributors, are also obliged to initiate or arrange for corrective measures in the event of non-compliant packaging and to notify the authorities in all Member States in which the packaging was made available on the market. According to the wording of the regulation, both obligations should apply regardless of whether the non-conformity is associated with a risk for the recipient of the packaging.

Importers and distributors in particular are subject to certain verification obligations with regard to the proper fulfillment of obligations by manufacturers in accordance with Art. 18 para. 2 and Art. 19 para. 2 PPWR.

IV. Extended producer responsibility

Finally, the previous obligations in connection with extended producer responsibility from the Packaging Directive are transferred to Art. 44 ff. PPWR. The central actor for this is and remains the producer, who is generally the person who is established in a Member State and makes packaging available on the market for the first time in that Member State (Art. 3 No. 15 PPWR). In this context, it is important to note that the roles of the producer and the manufacturer must be considered and assigned separately.

In terms of content, at least the basic framework of national registration, responsibility for collection, take-back via systems and volume reporting obligations will be retained. In the context of system participation, reference should also be made to Art. 12 para. 9 PPWR, which has been systematically misplaced. This stipulates that in each Member State in which packaging is subject to an extended producer responsibility regime, compliance with the corresponding obligations must be indicated by means of a symbol in a QR code. The concrete effects of the numerous detailed changes in accordance with the requirements of the PPWR will only become apparent when the Member States adapt their national laws to the PPWR, whereby in Germany in particular it is possible that the distinction between packaging subject to system participation and packaging not subject to system participation may be abolished.

Finally, reference should also be made to the extended information obligations under Art. 55 PPWR, which are intended to be a further element for reducing packaging waste and preventing environmental pollution through littering by providing information to consumers.

Outlook

The PPWR will probably affect almost all manufacturing and retail sectors in one way or another. In combination with numerous ambiguities in the legislation, numerous practical interpretation and application difficulties are therefore to be expected in the initial phase. It is thus all the more important that affected market players prepare for the new requirements at an early stage, ensure the greatest possible clarity in their supply chains with regard to the allocation of obligations and help shape the future development of the law by participating in the numerous consultation procedures for delegated and implementing acts that are expected.

Overall, packaging law must be moved from the often assigned niche of extended producer responsibility to the center of attention in the future, as a legally compliant packaging design will be an essential prerequisite for the marketability of packaged products.

Do you have any questions about this news, or would you like to discuss it with the author? Please contact: Michael Öttinger