This is particularly true due to the increasing tendency of legislators to explicitly interlink different regulatory areas – for example, the inclusion of “substances of very high concern” in the regulatory system of Regulation (EU) 2024/1781 (“ESPR”) or the relevance of banned “chemical substances” for the assessment of the risk level in accordance with Annex II point 4.1 d) to Delegated Regulation (EU) 2024/3173.

The pending adoption of the regulatory package on the OSOA approach (“one substance – one assessment”) will further support this trend. In addition to a standardized data platform for information on substances, inter alia the reassignment of tasks to the European Chemicals Agency (“ECHA”) is also planned, for which a new basic regulation is to be issued at the same time.

This will further increase the importance of substance-related requirements in the field of product compliance. In addition to these future regulations, there is also the need to comply with and implement numerous legal amendments from previous years, which will now come into force in 2025. This article highlights some key aspects that need to be kept in mind.

A. REACH

With regard to the REACH Regulation, various aspects are relevant that deserve attention in 2025.

I. Revision

Even though this process has recently come to a significant standstill, a revision of Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 (“REACH”) is still pending. Even under the new Commission, efforts to simplify the legal requirements remain an integral part of the political agenda. The amendments are to form part of a future “Chemicals Industry Package”. While extensive proposals have already been drawn up and submitted by industry, the Commission’s political agenda in this area has yet to be fleshed out. It remains to be seen whether and to what extent the Commission will take up or modify previous considerations on the revision of REACH. The focus here is on the revision of authorisation and restriction procedures, including the introduction of a generic risk assessment approach, the extension of registration obligations (e.g. to certain polymers) or the expansion of data requirements. The further implementation of requirements in accordance with the “safe and sustainable by design” concept, the introduction of “non-toxic material cycles” and the establishment of an “essential use concept” will also continue to be the focus of the revision of REACH.

II Substance and dossier evaluation

On December 10, 2024, ECHA submitted a draft update of the “Community Rolling Action Plan (CoRAP)” for the years 2025 to 2027. For the year 2025, four substances already addressed in the CoRAP are planned for further evaluation, while a further four substances have been added for the year 2025.

ECHA has already pointed out that registrants of the substances concerned should review their respective registration dossiers and, if necessary, complete them by March 2025 to ensure that all necessary information is included.

In addition, all registrants should also bear in mind that the application of the hazard classes introduced by Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/707 and the associated hazard statements will become mandatory for substances placed on the market from 01.05.2025. The corresponding requirements should therefore also be taken into account in any dossier updates.

III List of candidates for authorisation

ECHA last updated the candidate list on 7 November 2024 and added another substance, triphenyl phosphate (EC: 204-112-2, CAS: 115-86-6). Since then, the candidate list has comprised a total of 242 entries, which must be taken into account directly both for communication in the supply chain in accordance with Art. 33 REACH and for notifications in the SCIP database. For any notification obligations under Art. 7 para. 2 REACH, a transitional period of a further six months applies to the most recently added substance (see Art. 7 para. 7 REACH).

If ECHA were to follow the established practice of two updates within 12 months, a further addition to the candidate list would not be expected until the middle of the year. However, ECHA departed from the usual practice with the addition to the candidate list on 07.11.2024 and made an additional, third addition to the list in 2024 (following the amendments of 23.01.2024 and 27.06.2024). The regular addition to the list of candidates at the beginning of 2025 is still pending. As can be seen from the minutes of the 88th meeting of the Member States Committee on 12.12.2024, a further addition to the candidate list is to be made as early as 21.01.2025, with which the following substances are to be added:

- Octamethyltrisiloxanes (EC: 203-497-4, CAS: 107-51-7);

- O,O,O-triphenyl phosphorothioate (EC: 209-909-9, CAS: 597-82-0);

- Reaction mass of: triphenylthiophosphate and tertiary butylated phenyl derivatives (EC: 421-820-9, CAS: 192268-65-8);

- Perfluamine (EC: 206-420-2, CAS: 338-83-0);

- Tris(4-nonylphenyl, branched and linear) phosphite (EC: -, CAS: -);

- 6-[(C10-C13)-alkyl-(branched, unsaturated)-2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl] hexanoic acid (EC: 701-118-1, CAS: 2156592-54-8).

This poses a number of challenges for affected companies, as communication processes in the supply chain now have to be reviewed or updated in quick succession.

IV. Authorisation requirements

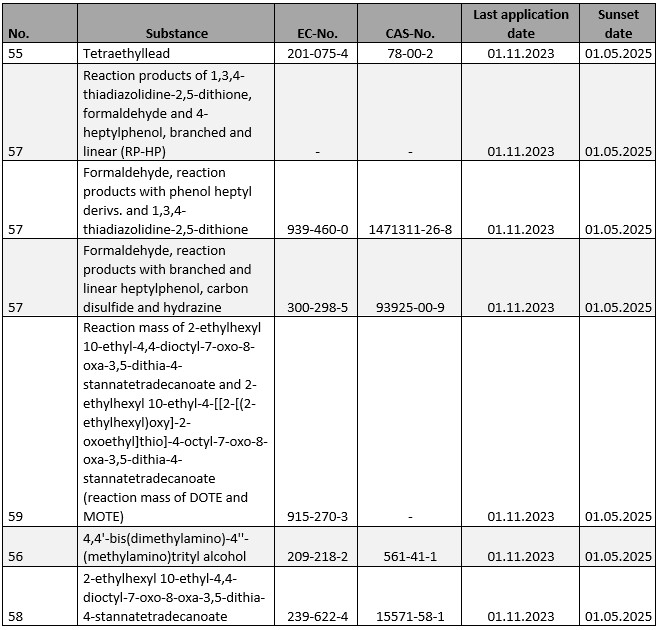

For a number of substances subject to authorisation in accordance with Annex XIV to REACH, the expiry date will be reached in the current year, i.e. the date from which the respective substance may no longer be used as such or as a constituent of mixtures, unless a corresponding application for authorization has already been submitted in due time before 01.11.2023 (see our outlook for 2023) or one of the few general exemptions intervenes . The following substances are affected:

It is worth mentioning that, according to the minutes of the 88th meeting of the Committee of Member States of 12.12.2024, the approach for prioritizing substances for inclusion in Annex XIV is also to be revised. In addition to a thoroughly appropriate, critical review and, if necessary, supplementation of the existing decision parameters, it would certainly be desirable if the prioritization process were also more transparent with regard to individual decision-making processes.

V. Restrictions

For a number of restrictions, previous exemptions or transitional regulations will expire in 2025, for example for

- the use of diaphragms containing chrysotile in electrolysis installations (see No. 6 in Annex XVII to REACH; deadline: 01.07.2025);

- the use of lead and its compounds in articles made from polymers or copolymers of vinyl chloride (“PVC”) if the concentration of lead is 0.1% or more by weight of the PVC material and if the articles contain recovered flexible PVC (entry No. 63 in Annex XVII to REACH; deadline: 28.05.2025);

- the use of C9-C14-PFCA, their salts and C9-C14-PFCA-related substances for (i) photolithographic or etch processes in semiconductor manufacturing, (ii) photographic coatings applied to films, (iii) invasive and implantable medical devices and (iv) certain firefighting foams (entry No. 68 in Annex XVII to REACH; cut-off date 04.07.2025)

- the use of N,N-dimethylformamide for placing on the market for use or for use as a solvent for dry and wet spinning of synthetic fibers (entry No. 76 in Annex XVII to REACH; deadline: 12.12.2025).

or further obligations are added for the first time, such as

- the obligation of suppliers of synthetic polymer microparticles as such or in mixtures for use in industrial plants to provide additional information and instructions in future (see entry No. 78 in Annex XVII to REACH, reference date: 17.10.2025);

- the obligation for suppliers of products placing synthetic polymer microparticles on the market in the form of a food additive to provide instructions for use and disposal to professional users and the general public explaining how to prevent the release of synthetic polymer microparticles into the environment ; the same obligation applies to suppliers of synthetic polymer microparticles,

- which are contained by technical means to prevent release to the environment when used as directed during the intended end use;

- whose physical properties are permanently altered during the intended end use in such a way that the polymer no longer falls within the scope of this entry;

- which are permanently integrated into a fixed matrix during the intended end use (see entry No. 78 in Annex XVII to REACH, reference date: 17.10.2025).

Irrespective of this, the further progress of the discussions on the proposal to restrict PFAS will of course continue to be monitored. Further discussions on sector-specific exemptions and transitional provisions are planned for the current year and new regulatory approaches are also to be discussed, according to the update on the process published at the end of last year.

B. CLP

Following the introduction of new hazard classes (EDs, PBTs, PMTs, etc.) by a delegated act in 2023, the year 2025 will be dominated by preparations for the implementation of the revised requirements of Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008 (“CLP”), which was recently amended by Regulation (EU) 2024/2865. This regulation, published in the Official Journal of the EU on 20.11.2024, amends specific requirements for the classification of substances with multiple constituents, provides for a new version of Art. 10 CLP regarding concentration limits, M-factors and acute toxicity estimates for the classification of substances and mixtures and introduces specific requirements for the supply of hazardous substances and mixtures via so-called “refill stations”.

However, the most practically significant complex of changes concerns aspects of labeling. The requirements for the design of labels (previously addressed in part by the corresponding guideline) have now been explicitly integrated into Annex I to CLP (e.g. on color, font type and size, line spacing, etc.). The regulations for updating labels in Art. 30 CLP have also been updated and clarified.

Chemicals legislation has rightly always been a cross-cutting issue of product legislation. The new version of CLP now takes this up in concrete terms and provides in Art. 25 para. 9 CLP, for example, that label elements resulting from requirements of other Union legal acts must be included in the section with supplementary information on the label (according to CLP!). This means that such requirements are uno actu also subject to the specific design requirements and format specifications of the revised CLP. This is because the section with supplementary information is also an element of the label and is therefore also subject to the design requirements according to Section 1.2.1.5 in Part 1 of Annex I to CLP.

This alone shows that suppliers of hazardous substances and mixtures will face significant changes in the coming years, which will require early preparation. Regulation (EU) 2024/2865 provides for transitional provisions for the application of the new requirements (until 01.07.2026 and 01.01.2027, respectively) and also introduces an additional sell-off period until 01.07.2028 or 01.01.2029 for “old stocks” already in the supply chain. However, goods that are placed on the market for the first time after the date of application or that are to be placed on the market after expiry of the sell-off periods must meet the new requirements (see Art. 61 paras. 7, 8 CLP) in order to avoid a marketing ban (see Art. 4 para. 10 CLP). Even if the transitional provisions seem comparatively generous, the timeframe for cleaning up entire supply chains and any stocks remains ambitious.

C. Biocides

In biocide law, both EU legal developments in the BPR and national developments in the ChemBiozidDV must be taken into account for the year 2025.

I. BPR

At European level, the main focus continues to be on proceeding with the work program under Regulation (EU) No 528/2012 (“BPR”), together with the corresponding update of the relevant Delegated Regulation (EU) No 1062/2014. ECHA points out any deadlines for 2025 in the usual way here.

In this context, additional data requests are also recorded in pending procedures for active substance approval or product authorization. Applicants should also be prepared for this in 2025 if the evaluating authorities see reason to do so due to the adjustments and updates to guidelines and recommendations for the evaluation. In this context, the “BPC Recommendations” for the assessment of so-called “in-situ” systems, which are expected for spring 2025, will also be of particular relevance. More than 12 years after the BPR came into force, these are intended to specify the framework conditions for the data requirements and assessments of in-situ systems in a way that takes into account the actual and technical peculiarities of the on-site production of biocidal products – and also reveal in detail how little the BPR had such systems in mind, even though they were expressly included in the scope of application from the outset. For practical approaches, the legal requirements of the BPR will at least have to be “stretched” considerably. Overall, however, it is to be welcomed that ECHA and the competent authorities of the Member States have dedicated themselves to the topic with great commitment, in order to provide more clarity to the relevant procedures – also in the interests of the applicants.

II. ChemBiozidDV

At national level in Germany, the year 2025 has already started with the introduction of the ban on self-service offers and the application of further sales restrictions for certain biocidal products in accordance with the ChemBiozidDV. Since 01.01.2025 a self-service ban applies to biocidal products,

- if one or more uses of these products are not permitted for the general public according to the labeling specified by the authorisation in accordance with the BPR; or

- which are still marketable without authorisation according to the BPR due to applicable transitional provisions and are assigned to product types 14, 18 or 21 according to Annex V of the BPR,

i.e. these products may only be offered and dispensed in a form in which the purchaser does not have free access to the biocidal product (see Sec. 10 para. 1 No. 2 ChemBiozidDV).

In addition, the purchaser must be given further verbal instructions (see Sec. 10 para. 2 in conjunction with Sec. 11 ChemBiozidDV), further requirements apply to online and mail order sales (Sec. 12 ChemBiozidDV) and the sale may only be facilitated by a person who has sufficient expertise as required for the sale (Sec. 13 ChemBiozidDV).

Furthermore, biocidal products that are subject to transitional provisions in accordance with the BPR and are assigned to product types 7, 8 or 10 according to Annex V of the BPR may only be placed on the market if organisational measures ensure that the further oral instruction of the purchaser (see Sec. 10 para. 2 in conjunction with Sec. 11 ChemBiozidDV) is carried out by a sufficiently qualified person (Sec. 13 ChemBiozidDV).

D. POP

Further amendments to Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 (“POPs”) are expected in 2025, after the list of substances included in the underlying Stockholm Convention has already been expanded. The EU’s legal framework still needs to be adapted accordingly.

Beyond this rather formal readjustment of the European legal framework, however, a new interpretation document from the European Commission is causing quite a stir. The document presents a new understanding of the exemption under Art. 4 para. 2 POPs for substances that are present in articles that were already in use before or at the time since the POP Regulation or its predecessor regulation applies to these substances – whichever is earlier. This exemption has so far been interpreted very broadly due to the specifically defined term “use” (see Art. 2 No. 6 POP, which refers to the definition of the same term in Art. 3 No. 24 REACH), as this term includes literally “any utilization” (including storage, for example).

Now, however, use within the meaning of Art. 4 para. 2 POP shall require that the product concerned is already in the possession of the end user. As a result, goods that are still in the supply chain – e.g. in stock at a retailer – but have not yet reached the end user at the corresponding application date would no longer benefit from the exception. Such goods would no longer be marketable and would even have to be disposed of as waste (see Art. 5 para. 1 POP).

The impact of this reinterpretation can hardly be overlooked at present. Of course, the practical relevance will also depend on the level of enforcement. However, the (unexpected) discontinuation of the marketability of inventories alone will cause considerable discussion in countless supply relationships this year if contractual claims or general requirements from a material and product compliance perspective are taken into consideration.

Conclusion and outlook

Chemicals legislation will remain a demanding subject in 2025 and will continue to present companies with considerable challenges. Comparatively low-threshold changes that are often implemented outside the sphere of perception of affected companies – e.g. by merely changing the classification of a substance, extending prohibition regulations to groups of substances or substances/mixtures with certain properties or even changing mere interpretations – can have a considerable economic impact. Without sufficient sensors to detect such developments in the area of material compliance at an early stage, companies in production and trade will no longer be able to act in a targeted manner on the market – or even be able to defend their interests in consultation, application or appeal proceedings at an early stage.

Do you have any questions about this news or would you like to discuss it with the author? Please contact: Martin Ahlhaus